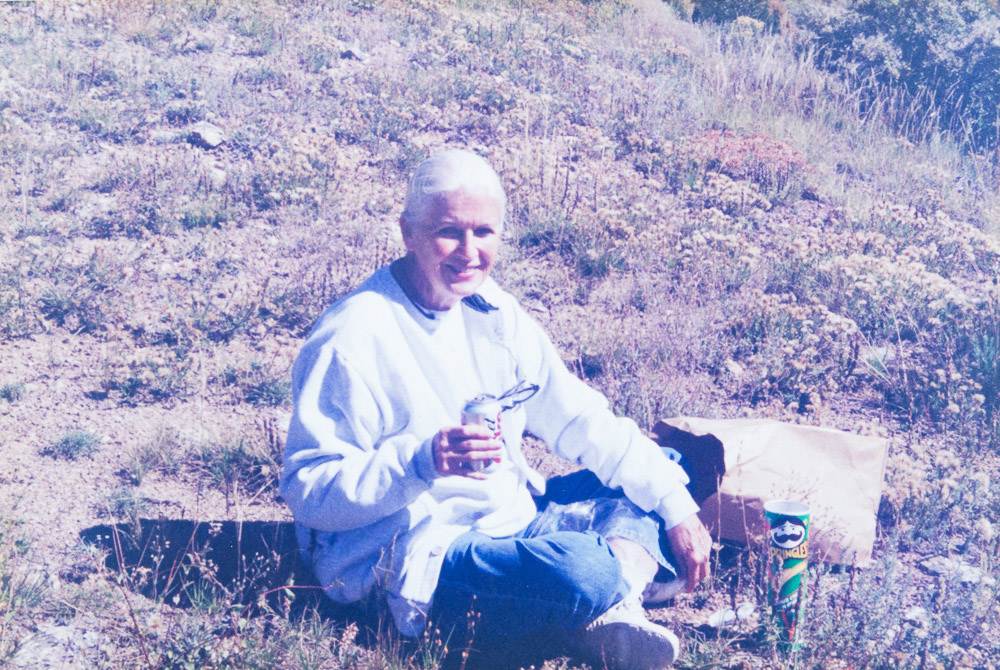

Roy C. Coffee, Jr

June 27, 2017Joan Hughston Book

May 8, 2018

Roy C. Coffee, Jr

June 27, 2017Joan Hughston Book

May 8, 2018

Joan Palmer Hughston Memorial

Courtyard Garden Dedication

Millicent Rogers Museum,

Taos, New Mexico, 6 September 2003

It is an honor and privilege to be able to address a few words to you today on behalf of my mother’s family on the occasion of the dedication of this garden courtyard, which will be made so beautiful by the inclusion of native and local plants and flowers. The idea of such a planting was one that she had been very keen on herself during her years as a member of the Board of Trustees of the Millicent Rogers Museum, and it is undoubtedly the case the she would have been very pleased with this.

It is wonderful that so many of my mother’s friends and relatives have taken the trouble to be here today, including a number who have traveled from out of state, and we would like to welcome you all, and thank you so much for coming. It is especially nice to have Joan’s two cousins Joyce Semple from California and Susie Bradstock from Arizona.

One person whom we would all have liked to have seen here is Joan herself. Alas that cannot be. But with the hope perhaps of bringing back her spirit for a few moments, I thought that perhaps the best way to proceed would be to let the rest of my remarks in fact be hers.

In conclusion therefore let me take a few minutes to read to you an excerpt from one of the various notebooks she kept in which she wrote tales about her childhood. This is a part of her background with which most of you will be unfamiliar, and will thus possibly be all the more interesting.

Here in what follows she writes about an exciting formative vent in her life that occurred when she was about ten or eleven years old.

A Rainy Day in New Orleans, 1939

One unusually dark September morning in New Orleans, about 1939, I lay in bed and listened to the rain and gusty wind, the backlash of a tropical storm which had shaken and pounded on our house for hours. I could hear Mama and Daddy talking in the kitchen. They had been up most of the night shifting pans under roof leaks and putting folded towels along window sills – and cold cloths on my forehead.

In the midst of the storm I had suffered an ill-timed bad attack of the malaria that had plagued me for six months; and the prescribed medications, quinine, had dealt me its usual severe headache. Chills, fever, and storm subsided with the night, and morning came, and things seemed much better as they always do.

Daddy came in, kissed me goodbye, and left for the office. Mama changed my bedclothes and fixed breakfast while I bathed and put on a clean gown. After eating, I felt well enough to want to do something. My activities were limited to quiet play in my room: the dollhouse Mama and Daddy made for Christmas stood on the floor close to my bed; my paint box, paper and pencils, new Nancy Drew books, small radio, Ovaltine Secret Decoder Badge, and a cigar box full of paper dolls were on the little desk that served as a bedside table. The bookshelves across the room held, among other treasures, The Blue Fairy Book, Lorraine and the Flower People, a complete set of the Book of Knowledge and Lands and People, several “big little” books, a few comic books, a Monopoly game, sets of dominoes and checks, ten metal jacks and a small red rubber ball, and a Philo Vance mystery checked out of the library for me by my friend Harold wo was trying to improve my mind. My Shirley Temple doll and Duz Dap, our cat, sat beside me on our bed.

I was anxious to play while I felt well before lunchtime because the malaria would probably return with a sudden angry flush as it did most afternoons, at which time I could only lie down and sleep or listen to the radio. Either the medicine or the disease made me dizzy if I moved my head, so I learned to be very still during this time and forget my miseries by listening to those of Ma Perkins et al. By the time Jack Armstrong and Orphan Annie came on I usually felt better and when the Lone Ranger rode in I was ready to sit up again.

Even though I could entertain myself pretty well with all these prized possessions, I missed the outside world of roller-skating, jumping rope, flying kits, swimming, visiting the zoo, going to school, and most of all, being with my friends. Mama realized this and was ingenious at creating new diversions.

This particular morning she came back into the room with a surprise, a large cardboard box which she sat down beside me. Opening it I found three things: a very old shaggy scrapbook bulging with all sorts of strange items, a small old leather book, and another box containing old photographs and daguerreotypes. Mama explained that these had all belonged to Daddy’s grandmother, my own great-grandmother who I had never known because she had died before I was born, but who, as a small girl my age, had also lived in New Orleans, and who had pasted things in the very scrapbook I then held in my lap, and who had kept a diary, the little leather book.

I was curious about her as you sometimes are about a new friend you immediately like. Mama told me her name was Ida Purcell and showed me several pictures of her, and her family, and even one of her nursemaid Anne Purcell – who was a slave, for this was during Civil War time.

Then she showed me a picture of her several years later as a pretty young woman wearing a riding habit. That did it! I, of course, loved horses as most girls my age did and still do, and I wanted to know more and more about this interesting “new friend”. Mama suggested many answers and surprises were probably in the diary and scrapbook. She was right. I’ve been reading them more than forty-five years and am still finding answers, surprises, and more questions.

Inside the front cover of the diary was a faded in inscription, “To Ida Purcell from her Mother, September 1865.” A blank page followed. But the next page, which was contained Ida’s first entry in the little book, had been ripped out, leaving only jagged edges. Luckily, what had been written there faded against the preceding blank page and left a complete mirror image of the missing worlds. Well trained by Nancy Drew and Philo Vance, I had only to use a small hang mirror to read, “Today the Yankees chained a soldier in the square…”.

I do not know who tore out the page or why, but the account as seen through the eyes of a child my age made very clear what life was like in an occupied city during wartime. History books never made anything quite so clear. Wartime was also a common topic in 1939 even among us children because of what was going on in Europe that year, but also because New Orleans still felt and voiced great resentment and hurt from the War Between the States, and “Yankees” were not highly regarded at all. I guess I pictured Ida and her family (our family) as refugees out of “Gone with the Wind”. My class at school visited the Confederate Home every year and talked to the old men – one of whom was 102 years old.

I was really shocked to discover that Ida’s mother had died only one month after giving Ida the diary, and that, unbelievably, her father had died the month following that. It was terrible to think of this little girl, my “new friend”, suddenly left so alone and sad. Who would take care of her? Where would she live? What would become of her? The answers were in the diary and photographs, like pieces of a puzzle put together. What I found, Ida’s complete story, can be found in my biographies of the Purcell and Palmer families.

I have told you this one short tale not only to explain the beginning of my interest in family history, but also to encourage you to look deeply into your past, and appreciate these real people who were your ancestors and without whom you would not exist. A part of each of them lives in you.

You will enjoy knowing some more than others. We know of some who lead exceptionally exciting lives, and other who came to very unusual ends; for instance, just offhand I can think of three who were scalped by Indians, three who died as accused witches in Massachusetts, one who died scaling the walls of Acre during the crusades, and one, a soldier, who, unhappily, was drawn and quartered by his own men!

So never make the mistake of thinking of them as colorless, doddering, old boring people. Always remember that they too were once children, who had friends who grew up, fell in love, had all sorts of adventures, eventually married, had an occupation—and hopefully came to a better end than being drawn and quartered.

Also remember that you yourself are in the process of becoming part of your own family’s history. So mind your behaviors, and leave a creditable record. Someone my someday be reading about you. And wondering.

Joan Palmer Hughston (1928-2003), written in Taos about 1984

~ Remarks by Lane Palmer Hughston

One unusually dark September morning in New Orleans, about 1939, I lay in bed and listened to the rain and gusty wind, the backlash of a tropical storm which had shaken and pounded on our house for hours.